Home > Nahant > Essays

For Such a Small Place: Poetry by the Sea

in Nahant

By Carl  Carlsen

Carlsen

Nahant. For such a small place, for just 3600 people, for

a place without a stoplight, there’s a lot of poetry.

What is it about Nahant that produces so much poetry, that

makes Nahant so poetic?

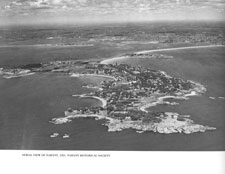

It’s geography that makes Nahant special. Nahant is

two islands connected to Lynn by two tombolos (a tombolo

is an isthmus that floods at high tide). In the old days,

the tombolos made Nahant a sort of magical place, or at least

one linked to the rhythms of nature since tide tables determined

when to cross to Nahant and when to return. Alonzo Lewis’ poem, “Nahant

Song” described the trip this way:

. . .O’er the shining sand

Far out in the tide, away from land;

And

we seem in the middle air to go,

With the sky above and the sky below!

Little Nahant is a forty acre triangle and Big Nahant

is a square mile  boomerang.

Theirs is a long shoreline of rocks and sand beaches that

has always fascinated poets, and for such a small place,

there are a lot of rocks and a lot of beaches. There’s

Long Beach and Short Beach before

you even get to Big Nahant, and from there, clockwise around

Big Nahant, it’s Stony Beach, Forty

Steps Beach, Canoe Beach, Joseph’s Beach, Curlew Beach,

Wharf Beach, Tudor Beach, Dorothy’s Beach, Pond Beach,

and finally Black Rock Beach. Then there are the

boomerang.

Theirs is a long shoreline of rocks and sand beaches that

has always fascinated poets, and for such a small place,

there are a lot of rocks and a lot of beaches. There’s

Long Beach and Short Beach before

you even get to Big Nahant, and from there, clockwise around

Big Nahant, it’s Stony Beach, Forty

Steps Beach, Canoe Beach, Joseph’s Beach, Curlew Beach,

Wharf Beach, Tudor Beach, Dorothy’s Beach, Pond Beach,

and finally Black Rock Beach. Then there are the  points

(protruding rocks), again going clockwise around

the boomerang from Short Beach: John’s Peril,

Mifflin’s

Point, East Point,

Bass Rocks, Bass Point, and Black Rock Point. Then

there are places with poetic names: Egg Rock, Pulpit Rock,

Castle Rock, Spouting Horn, Swallows’ Cave,

Pea Island. And then there is Little Nahant

with Wolf ’s Cove, Eastern Point, East Cliff, Fox Caverns,

Great Furnace, Mary’s Grotto, Simmons Spring, and Little

Furnace. For such small islands to have so many place names

(and these are not all of them!) suggests a strong connection

between Nahanters and their home.

points

(protruding rocks), again going clockwise around

the boomerang from Short Beach: John’s Peril,

Mifflin’s

Point, East Point,

Bass Rocks, Bass Point, and Black Rock Point. Then

there are places with poetic names: Egg Rock, Pulpit Rock,

Castle Rock, Spouting Horn, Swallows’ Cave,

Pea Island. And then there is Little Nahant

with Wolf ’s Cove, Eastern Point, East Cliff, Fox Caverns,

Great Furnace, Mary’s Grotto, Simmons Spring, and Little

Furnace. For such small islands to have so many place names

(and these are not all of them!) suggests a strong connection

between Nahanters and their home.

Another thing that’s special about Nahant is all the

doubling going on.  There

are the two Nahants, Little Nahant and Big Nahant, and the

two tombolos, one separating Little Nahant from Lynn, and

the other connecting Little Nahant to Big Nahant. The two

islands and the two tombolos create Long Beach and Short

Beach. And not only is

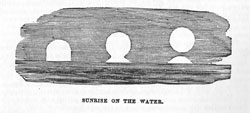

the doubling geographic, it’s visual too. Alonzo

Lewis, in his History of Lynn, provides illustrations

of a unique optical illusion seen near Nahant.

There

are the two Nahants, Little Nahant and Big Nahant, and the

two tombolos, one separating Little Nahant from Lynn, and

the other connecting Little Nahant to Big Nahant. The two

islands and the two tombolos create Long Beach and Short

Beach. And not only is

the doubling geographic, it’s visual too. Alonzo

Lewis, in his History of Lynn, provides illustrations

of a unique optical illusion seen near Nahant.  A

double image of the sun or a ship, one in the sky and one

in the water, occurs when certain cloud conditions prevail. In

Nahant’s poetry, the image of the double ship appears

in Nathan Ames’ epic “Pirates'

Glen and Dungeon Rock,” and then there is the double

sky in Lewis’ “Nahant

Song.”

A

double image of the sun or a ship, one in the sky and one

in the water, occurs when certain cloud conditions prevail. In

Nahant’s poetry, the image of the double ship appears

in Nathan Ames’ epic “Pirates'

Glen and Dungeon Rock,” and then there is the double

sky in Lewis’ “Nahant

Song.”

Doubling is what metaphor, the heart of poetry, is all about. Metaphor

is defined as speaking of one thing as if it were another. Doubling

could also refer, as metaphor does, to the literal (surface)

and figurative (hidden) meaning of things, and to the performance

of “feats of association,” as Robert Frost capsulized

the process of making metaphors.

As

a symbol and an island, Nahant stands alone as a separate

land embodying beauty and serenity. The sea and the

sky, so prominent in Nahant’s landscape, represent

the fluidity and changeability of life, while the rocks of

Nahant: Egg Rock, Pulpit Rock, and Castle Rock, evoke stability

and permanence.

As

a symbol and an island, Nahant stands alone as a separate

land embodying beauty and serenity. The sea and the

sky, so prominent in Nahant’s landscape, represent

the fluidity and changeability of life, while the rocks of

Nahant: Egg Rock, Pulpit Rock, and Castle Rock, evoke stability

and permanence.

Nahant’s physical features make it an oasis of  nature

in a modern world. In the age of industrialization,

the reforestation of Nahant, as well as the creation of a “garden” by

Ice King Frederic Tudor, illustrate how Nahant was a breath

of nature among the smokestacks. In modern times, the

conflict between nature and “civilization” is

sometimes won by nature on Nahant, as evidenced by two poems

written in the context of World Wars I and II: Charles Hammond

Gibson’s “The

Forty Steps” and Sara Teasdale’s, “Nahant.”

nature

in a modern world. In the age of industrialization,

the reforestation of Nahant, as well as the creation of a “garden” by

Ice King Frederic Tudor, illustrate how Nahant was a breath

of nature among the smokestacks. In modern times, the

conflict between nature and “civilization” is

sometimes won by nature on Nahant, as evidenced by two poems

written in the context of World Wars I and II: Charles Hammond

Gibson’s “The

Forty Steps” and Sara Teasdale’s, “Nahant.”

With geography, physical features, place names, and doubling

as a foundation, the poetic traditions of Nahant have been

established by the poets whom the islands have inspired. Chief

among these is Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who summered on

Nahant during most of the last half of the 1800’s,

a time that saw the blossoming of American literature and

the blossoming of the poetry of Nahant as well. Although

Longfellow’s stature alone may be enough to give Nahant

a place in the history and catalog of American poetry, other

famous American poets like John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver

Wendell Holmes, and Sara Teasdale wrote poems about Nahant

as an island of serenity and beauty in a turbulent ocean.

Throughout Nahant’s history, its poetic qualities

and traditions have also inspired its year round residents.

Nahant’s most famous homegrown poet, Annie Johnson,

known familiarly as “Annie of Nahant,” was a

prominent regional poet during the age of Longfellow and

of industrialization. More recently, Nahanters have

shown their support for the poetry of Nahant residents by

publishing two anthologies: Written Words by Nahanters (1976)

and Nahant Voices (1984). How Nahant inspires

the poetic vision of its residents is perhaps best shown

by Robert Risch’s poem, “Beach

Pebbles,” which

tells how a gift from his sons made him regard a beach pebble

as more than just a stone. Today, many practicing poets

are inspired by Nahant.

Throughout Nahant’s history, its poetic qualities

and traditions have also inspired its year round residents.

Nahant’s most famous homegrown poet, Annie Johnson,

known familiarly as “Annie of Nahant,” was a

prominent regional poet during the age of Longfellow and

of industrialization. More recently, Nahanters have

shown their support for the poetry of Nahant residents by

publishing two anthologies: Written Words by Nahanters (1976)

and Nahant Voices (1984). How Nahant inspires

the poetic vision of its residents is perhaps best shown

by Robert Risch’s poem, “Beach

Pebbles,” which

tells how a gift from his sons made him regard a beach pebble

as more than just a stone. Today, many practicing poets

are inspired by Nahant.

So Nahant in itself is poetic, in its geography and in its

natural beauty. Throughout its history, Nahant’s

scenery, serenity, and isolation have inspired its poets,

from the most ordinary to the most extraordinary.

Nahant and poetry belong in the same breath.