Lynn Woods Reservation is the largest municipal park in New England, over twice the size of Central Park in New York City, and the third largest municipal park in the northeast United States. It occupies 2200 acres in the northeast corner of Lynn, abutting and also including portions of Saugus and Lynnfield. The Gannon Municipal Golf Course (originally named Happy Valley) is within the boundary of Lynn Woods, and nearby is the Pine Grove Cemetery, established in 1850 as one of America’s first garden cemeteries. Thus, this large area of Lynn brings its residents close to Nature in a variety of ways.

Lynn Woods Reservation is 3 miles from Lynn’s Central Square and 11 miles from Boston. The land was initially held in common by Lynn's first European settlers, then owned privately, and since the 1890s has been again held in common by the city as a natural refuge for its residents. Lynn Woods takes up one fifth of the city’s land area and is managed by park ranger Dan Small together with the Lynn Water and Sewer Commission, Department of Public Works, Park Commission, and Department of Economic Development.

History and Legends

Dungeon Rock and early Lynn Woods history

When Europeans first arrived in Lynn in 1629, they began to use the forest now known as Lynn Woods Reservation as a source of timber and fuel. The first literary rendering of Lynn’s woods appeared in 1634 in New England’s Prospect by William Wood. The work praised the extraordinary quality of the woods’ waters. In 1686, European settlers bought the woods and the surrounding area from the Pawtucket Indian tribe for $75, and the woods were held in common until 1706, when proportionally allocated individual tracts were created for the town’s landowners. During this early period of European settlement, in 1658, an earthquake occurred which has served as a historical anchor for the popular legend about Dungeon Rock and its buried pirate treasure.

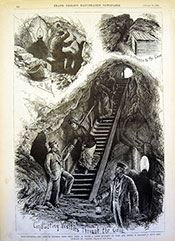

The legend is about pirates who traveled up the Saugus River in order to exchange silver for shackles, perhaps made at the Saugus Iron Works. They buried their treasure in a cave at Dungeon Rock, only to have the lone remaining pirate, Thomas Veal, entombed with the treasure by the earthquake of 1658. The story of the legend was published for the first time by Alonzo Lewis in his 1829 History of Lynn. The legend was expanded into an epic romantic poem, “Pirates’ Glen and Dungeon Rock,” by Nathan Ames in 1853, and in 1983, Saugus historian Richard Provenzano published the definitive study, Pirates’ Glen and Dungeon Rock: The Evolution of a Legend (Saugus MA: Saugus Historical Society). The Swampscott Public Library has

detailed the story, and it is clear that the legend and the possibility of buried treasure at Dungeon Rock intrigue all who know about it.

In the mid-nineteenth century, three events occurred which set the stage for the modern, twentieth century incarnation of Lynn Woods. In 1843, Theophilus Breed formed the 50 acre Breed’s Pond to power his iron works by damming local streams. This began the change in focus from wood to water as the central resource of the Woods and set a precedent for restructuring the water system of the Woods. In 1850, Lynn naturalist and poet Cyrus Tracy and three of his friends formed the Exploring Circle, an organization devoted primarily to investigating and describing the natural wonders of Lynn Woods and encouraging others to experience the beauty of the area. The Exploring Circle morphed into the Trustees of the Free Public Forest, which became absorbed by the city’s Board of Park Commissioners. All three organizations contributed to what was, in America, a pioneering effort to secure recreational wilderness space for urban residents. And, in 1851, Hiram Marble began an excavation at Dungeon Rock in search of Thomas Veal’s pirate treasure, a labor which lasted nearly 30 years, as it was continued after his death in 1868 by his son Edwin. And so, in mid-nineteenth century Lynn was born the present day character of Lynn Woods: a combination of Nature’s treasure and buried treasure.

In the mid-nineteenth century, three events occurred which set the stage for the modern, twentieth century incarnation of Lynn Woods. In 1843, Theophilus Breed formed the 50 acre Breed’s Pond to power his iron works by damming local streams. This began the change in focus from wood to water as the central resource of the Woods and set a precedent for restructuring the water system of the Woods. In 1850, Lynn naturalist and poet Cyrus Tracy and three of his friends formed the Exploring Circle, an organization devoted primarily to investigating and describing the natural wonders of Lynn Woods and encouraging others to experience the beauty of the area. The Exploring Circle morphed into the Trustees of the Free Public Forest, which became absorbed by the city’s Board of Park Commissioners. All three organizations contributed to what was, in America, a pioneering effort to secure recreational wilderness space for urban residents. And, in 1851, Hiram Marble began an excavation at Dungeon Rock in search of Thomas Veal’s pirate treasure, a labor which lasted nearly 30 years, as it was continued after his death in 1868 by his son Edwin. And so, in mid-nineteenth century Lynn was born the present day character of Lynn Woods: a combination of Nature’s treasure and buried treasure.

Establishing Lynn Woods Reservation

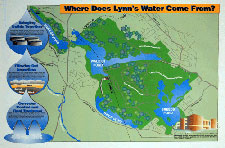

The catastrophic Lynn fire of 1869 began the transform ation of the water system of Lynn Woods into its current configuration of ponds. In order to ensure a water supply for the growing industrial city and to have enough water for future conflagrations, the Lynn Water Board was established in 1870 and promptly purchased Breed’s Pond later that year. In 1878, Birch Pond was created by damming streams and in 1888 and 1889, dammed streams created Walden and Glen Lewis Ponds, which were combined to form an enlarged Walden Pond between 1900 and 1905. The expansion and consolidation of the city’s water supply in Lynn Woods during this period proved prescient given the historic Great Fire of 1889 and the growth in the city’s population from 28,000 in 1870 to 68,000 in 1900. The Water Board’s success in protecting the city’s water supply contributed to the effort to preserve the surrounding land of Lynn Woods, and in so doing, created a combination of water and wilderness similar to Dogtown in Gloucester.

ation of the water system of Lynn Woods into its current configuration of ponds. In order to ensure a water supply for the growing industrial city and to have enough water for future conflagrations, the Lynn Water Board was established in 1870 and promptly purchased Breed’s Pond later that year. In 1878, Birch Pond was created by damming streams and in 1888 and 1889, dammed streams created Walden and Glen Lewis Ponds, which were combined to form an enlarged Walden Pond between 1900 and 1905. The expansion and consolidation of the city’s water supply in Lynn Woods during this period proved prescient given the historic Great Fire of 1889 and the growth in the city’s population from 28,000 in 1870 to 68,000 in 1900. The Water Board’s success in protecting the city’s water supply contributed to the effort to preserve the surrounding land of Lynn Woods, and in so doing, created a combination of water and wilderness similar to Dogtown in Gloucester.

Changes in the politics of Lynn Woods accompanied the reshaping of its water system. In 1881, Cyrus Tracy and the Exploring Circle transformed themselves into the Trustees of the Free Public Forest, an organization that spearheaded a movement to purchase Lynn Woods acreage in order to ensure the forest would be held in common and remain intact in perpetuity. In 1882, the Massachusetts legislature passed the Park Act, which enabled cities and towns to create and establish parklands within their borders. In 1890, the Public Forest Trustees conveyed the land they had obtained to the city, the Board of Park Commissioners officially adopted the name Lynn Woods, and a flurry of activity erupted over the next decade to acquire as much land for the park as possible and to begin its development for public use.

In the mid-1880s, Cyrus Tracy stepped down as head of the Trustees of the Free Public Forest because of perceived financial irregularities, and Philip Chase took his place. Philip Chase was a tireless advocate of Lynn Woods, and in 1889, when the Lynn Park Commission inherited the work of the Trustees, Chase became its chairman. That same year, Chase wrote for advice about the park to Frederick Law Olmsted, godfather of American urban parklands and creator of New York’s Central Park and Boston’s Emerald Necklace. Olmsted toured Lynn Woods and wrote back to Chase with a recommendation that was taken to heart. In his letter, Olmsted stated Lynn Woods was better than a park or public garden; it was a “real forest” and should remain unspoiled, “supplying a place of refreshing and restful relief.” Chase served as chair of the Park Commissioners until 1893, when he was replaced by Nathan Hawkes, author of the classic In Lynn Woods with Pen and Camera (Lynn: Thos. P. Nichols, 1893). Interestingly, in 1897, Philip Chase became the first president of the Lynn Historical Society.

The 1890s was a golden period for Lynn Woods. The Board of Park Commissioners promoted Lynn Woods as an urban oasis and a “resort.” In 1891, the Lynn & Boston Railroad built a station at Great Woods Road. In 1893, the Commissioners established Park Police and wooden observation towers were built at Burrill Hill (1895) and Mt. Gilead (1900), Lynn’s two highest elevations respectively. This was a period of significant road building within the park and of debate with the Metropolitan Park Commission over the inclusion of Lynn Woods in a regional park including the Middlesex Fells and Breakheart Reservation. Eventually, the city agreed with the opinion of Nathan Hawkes and decided to preserve its autonomy over Lynn Woods and avoid the costs of belonging to a centralized system. Proof of how important Lynn Woods was to the city is evident in the climax of Mabel Ward’s “Anniversary Poem,” read during the three day celebration in 1900 of Lynn’s 50th year as a city. In the poem, Lynn Woods is “Where at her fairest Nature stands” and “gives rest and peace and joy.” Later the same year, the Lynn Daily Evening Item published a series of ten articles by naturalist Charles Lawrence entitled, “Short Walks in Lynn Woods.”

The 1890s was a golden period for Lynn Woods. The Board of Park Commissioners promoted Lynn Woods as an urban oasis and a “resort.” In 1891, the Lynn & Boston Railroad built a station at Great Woods Road. In 1893, the Commissioners established Park Police and wooden observation towers were built at Burrill Hill (1895) and Mt. Gilead (1900), Lynn’s two highest elevations respectively. This was a period of significant road building within the park and of debate with the Metropolitan Park Commission over the inclusion of Lynn Woods in a regional park including the Middlesex Fells and Breakheart Reservation. Eventually, the city agreed with the opinion of Nathan Hawkes and decided to preserve its autonomy over Lynn Woods and avoid the costs of belonging to a centralized system. Proof of how important Lynn Woods was to the city is evident in the climax of Mabel Ward’s “Anniversary Poem,” read during the three day celebration in 1900 of Lynn’s 50th year as a city. In the poem, Lynn Woods is “Where at her fairest Nature stands” and “gives rest and peace and joy.” Later the same year, the Lynn Daily Evening Item published a series of ten articles by naturalist Charles Lawrence entitled, “Short Walks in Lynn Woods.”

Lynn Woods in decline

Perhaps the intermittent gypsy moth infestations of Lynn Woods in the first decade of the twentieth century presaged the cycle of deterioration and restoration of the park for the rest of that century. In 1910, the Board of Park Commissioners issued their last annual report, and funding for that body decreased over the next twenty years. With funding low, roads fell into disrepair and usage of the park declined. In 1929, a 1 1/8 mile nature trail was created, but by the following year, it was completely vandalized. There were some bright spots in those years: a toboggan chute in 1924, the construction of a steel observation tower on Mt. Gilead in 1929, and the building of the nine hole Happy Valley Golf Course in 1929. The brightest achievement in that period was accomplished by Park Superintendent John P. Morrissey, who, despite an inadequate budget, was able to bring the beautiful Rose Garden into being. It became a popular place for photographs and weddings. Other notable additions to Lynn Woods in the following decades included the expansion of Happy Valley to eighteen holes in 1933, the construction of a stone observation tower on Burrill Hill in 1936, and the building of an amphitheater in 1954. However, in general, as America experienced the Great Depression, World War II and the Korean War, Lynn Woods declined over time until it emerged in the 1960s and 1970s as a torched car dump and a haven for gangs, not exactly what the Trustees of the Free Public Forest envisioned.

The degraded condition of Lynn Woods led to three attempts to repurpose the park contrary to the vision of Olmsted. During the mid-1960s, and again in the mid-1970s, the city considered plans to intensify recreational use of the park that were both times abandoned because of financial constraints. The most serious threat to Lynn Woods occurred in the mid to late 1960s when a proposal was made to run Interstate 95 right through the park. The efforts of the Connector Objector Committee of the Pine Hill Civic Association, led by Stanley Cooke (for whom Cooke Road is named) as well as other community action groups persuaded Massachusetts Governor Francis Sargent to scrap the plan in 1970. These threats to the park’s original purpose show how vulnerable it had become by the last quarter of the twentieth century. That vulnerability is illustrated in the closure of the park for a year after a hurricane in 1953 and in a subsequent temporary closure in 1978 as a result of arson and vandalism. By 1986, many roads in Lynn Woods were impassable and the two observation towers were inaccessible.

Lynn Woods revitalized

In 1985, two outcomes of the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Management’s decision to include Lynn Woods in the Olmsted Historic Landscape Preservation Program have led to the revitalization of the park that is evident to today’s visitor. A report by Keith Morgan, Elizabeth Hope Cushing and Katherine Boonin of the American and New England Studies Program at Boston  University was completed in 1986 and helped bring a multi-million dollar DEM Olmsted Restoration Grant to Lynn Woods in 1990. The researchers described Lynn Woods as a “haven for drug and alcohol users, vandals, car thieves, garbage dumpers and a generally degraded group from the population of the surrounding communities” and noted that during their six months on site, “the number of dismantled and burned cars increased dramatically.” Their vision for the future of Lynn Woods, including preservation, restoration, maintenance, security, public involvement and signage including mapping with coordinates, has largely been realized. And, the report itself provides the most comprehensive history of Lynn Woods available.

University was completed in 1986 and helped bring a multi-million dollar DEM Olmsted Restoration Grant to Lynn Woods in 1990. The researchers described Lynn Woods as a “haven for drug and alcohol users, vandals, car thieves, garbage dumpers and a generally degraded group from the population of the surrounding communities” and noted that during their six months on site, “the number of dismantled and burned cars increased dramatically.” Their vision for the future of Lynn Woods, including preservation, restoration, maintenance, security, public involvement and signage including mapping with coordinates, has largely been realized. And, the report itself provides the most comprehensive history of Lynn Woods available.

As an adjunct to the state’s DEM project, the city of Lynn formed an advisory committee, and together with landscape architects, formulated several plans for reviving Lynn Woods, one of which was to double the size of the Lawrence P. Gannon Golf Course so that it would take up a tract of land in the center of the park roughly bounded by Dungeon Rock, the Stone Tower, and the Steel Tower. Resistance to this idea led to the organization of The Friends of the Lynn Woods, a community action group incorporated in 1990. Their mission, to ensure the perpetual existence of the Lynn Woods as outlined by the 1881 Indenture of the Trustees of the Free Public Forest, has led them to be instrumental in the rejuvenation and continued improvement of Lynn Woods. Steve Babbitt, FLW President from 1989 - 1999 says, "Our primary accomplishment has been to create a political presence to let everyone know that the people are taking the park back." The group's first capital improvement within the park, which took four years to achieve, was the restoration of the Rose Garden, rededicated in 1994. Indeed, the Olmsted Restoration Grant and The Friends of the Lynn Woods have brought into fruition a second golden era for Lynn Woods, just about a century after the first.

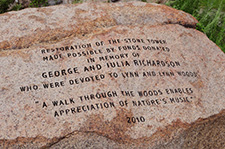

Today, thirty miles of scenic trails allow for nature walks, hiking, running, horseback riding, mountain biking, cross-country skiing, and bouldering. Lynn Woods hosts a series of summer cross-country running events, and the New England Mountain Bike Association encourages members to ride in the park. The Friends of the Lynn Woods sponsors the popular Kids’ Day at the amphitheater each July and the Dungeon Rock Pirate Day in October, which, according to local media, attracted more than 1200 people in 2011. The Lynn Woods Earth Fest, held in conjunction with Earth Day each April, brings Cub Scouts and students from North Shore Community College and Girls Inc. in Lynn to the park to help improve the grounds. In 2010, the Stone Tower on Burrill Hill was  restored to its former glory and a commemorative rock at the tower declares “A walk through the woods enables appreciation of nature’s music.” From the fall of 2010 through the spring of 2011, the Lynn Museum presented “Into Lynn Woods,” a major exhibition featuring the art and history of the park. And, in the summer of 2012, Arts After Hours inaugurated its Shakespeare in Lynn Woods program with a production of “Twelfth Night.” Clearly, with the supervision of super park ranger Dan Small, Lynn Woods today brings the vision of the Trustees of the Free Public Forest to life in the 21st century.

restored to its former glory and a commemorative rock at the tower declares “A walk through the woods enables appreciation of nature’s music.” From the fall of 2010 through the spring of 2011, the Lynn Museum presented “Into Lynn Woods,” a major exhibition featuring the art and history of the park. And, in the summer of 2012, Arts After Hours inaugurated its Shakespeare in Lynn Woods program with a production of “Twelfth Night.” Clearly, with the supervision of super park ranger Dan Small, Lynn Woods today brings the vision of the Trustees of the Free Public Forest to life in the 21st century.